Immersive learning

Immersive learning (eLearnExpo 2006: Paris, Moscow)

1. Overview

Most eLearning aims no higher than embedding information in the learner’s memory and then testing its recall with fact-based quiz questions. All this produces is learners who can identify, match, recognise or recall information. So what?

What managers need is staff who have been trained to accomplish tasks – this presentation showed examples of how this can be achieved.

2. Setting expectations – what will the eLearning achieve?

If an eLearning program is considered dull, the problem usually lies with a lack of imagination in defining the Learning Objectives, rather than any lack of sexy graphics or eye-popping animation; these are simply ‘cherries on the cake’. The effectiveness and impact of any eLearning are a direct product of – and are limited by – the ‘Learning Objectives’ we set. These are the tangible outcomes we must be able to measure on completion.Consider the key ingredients of a conventional eLearning project. You have one or more subject matter experts (SMEs) who have skills and experience, a vast body of existing information (documents, videos, images) and finally a workplace (sales office, production line, etc) in need of skilled staff. Hopefully there is an instructional designer and a project manager too.

In many cases the fundamental error is made at the outset of entrusting the definition of what is to be covered to the subject matter experts, not to the line manager in the workplace. The result is that the experts will feel obliged to cover far too much information and in unnecessary detail, in the mistaken belief that this is what workers need in order to become (like them) ‘experts’. “It’s taken me 14 years to get where I am today … so you’ve got an awful lot to learn.”

If SMEs have control of the scope of content, you are doomed to deliver an over-complicated program whose principal mission will be to expose the learner to information, often in isolated units.

Think of the sort of information which often gets included in traditional eLearning but which has no practical value to the learner in his job …

- Bar graphs and pie charts of market share, sales growth, reliability data, etc.

- Product specifications (capacities, speeds, temperatures, volumes, power, etc)

- Detailed Organisation charts (names, titles, departments, CVs)

- Thousands of words of background explanation

- Detailed Codes of Practice as defined by professional bodies

- Chapter and verse for laws affecting the learner in their jobs

Learners are not going to be able to remember all this information and, even if they could, what’s the point? Where is the context to apply it? Most people have access any time to all the information they could ever need to do their jobs: the Internet! Why try to pump data into people when Google is there waiting for them, an ‘uncomplaining servant’ at their instant command.

And the Learning Objectives for such ‘fact driven’ programs will be limited to measuring their information recall, using simple test questions such as:

- Which of the products shown is compatible with the Model 5000 range of toilet seats?

- In which year did Swindle Loans Inc. reach a turnover of $25M?

- Match the faults shown on the left with the relevant symptoms listed on the right

- True or False? David Finkelstein is CEO of Astroblob Inc.

- What is the output shaft diameter in mm of a DF1200A pump? Type in your answer.

Since the training had no greater ambition than a simple intake of information, how has this helped the learner in the real world? The truth is it hasn’t. For years we have believed that if we throw enough facts at employees some of it will stick and, if they are reasonably bright, they’ll be able to apply this wonderful new knowledge in their jobs.

I would make a distinction here between the education of students (where learning and the acquisition of knowledge needs to be empirical and typically has few practical, measurable outcomes in the short term) and the training of employees to perform tasks in the commercial world as effectively as possible.

If you had asked the learner’s line manager what he wanted the training to achieve you would get a very different set of objectives. His list of learning objectives might include the ability to:

- Correctly diagnose and repair a mechanical system within a set time and parts budget

- Determine the mortgage needs of potential customers and correctly select the most appropriate products

- Assess an emergency situation and within a limited time select the correct actions to be taken and their sequence

Notice that these objectives are not asking the learner to remember facts or figures. What the objectives are doing is posing them a challenge, presenting an opportunity to face a typical workplace task and to complete it to the best of their ability. This may require a certain amount of knowledge but more importantly, a clear understanding of what they need to do to accomplish the task and where to find the resources they might need along the way.

The ultimate purpose of commercial training is to produce competent staff. But what do we mean by ‘competence’? Certainly not an encyclopaedic knowledge of the company’s history or every last detail of your product specifications. ‘Competence’ is demonstrated when a person is able to call upon their knowledge and experience and apply them skilfully and using good judgement to complete a task satisfactorily (ie: to a set performance criteria). No eLearning program can be expected to achieve all of this because skill, judgement and ultimately wisdom only come in time in the real world.

This presentation suggested a practical approach to challenge your learners with work-relevant tasks to help them discover the limits of their knowledge and ability, to fill those gaps and finally to demonstrate they have developed real world problem-solving ability.

Some of his peers however are comparing notes and asking each other for guidance. A few of them are reading books, searching web pages or wringing their hands. In other words the competence of the group will vary significantly and the instructor will take into account all the actions of each person before arriving at an individual assessment. Little would have been achieved by giving the group a test of knowledge; what really mattered was how quickly and effectively each of them arrived at the solution.

3. Key features of immersive learning

The most immediate difference a learner will see is that he is not being asked to study many screens of information. From the outset he is given a task to complete. If he is already experienced, this may take him only a few seconds, and he can move on to another (perhaps more challenging) task.

But if he gets stuck and doesn’t know where to start then the program must be able to show him the way with narration, reference text, illustrations or video. If he still has difficulties then the program should gradually feed him hints and tips (as an expert colleague would if he was standing next to him). “Have you tried this …?” or “Change this part first, then see what happens.”

What we are doing is creating a learning environment in which people can experiment, attempt without injury or punishment outrageous things (possibly dangerous, expensive or simply extravagant), apply all their existing knowledge and judgement and ask for help when they need it.

But that same safe ‘sand pit’ in which they have played can also become a more serious ‘assessment room’ in which every step is measured and recorded. The investment in immersive programs, although more costly to create than traditional eLearning content, therefore has a double pay-back.

Regardless of complexity or subject matter, immersive learning programs should have as many of the following features as possible:

- Highly realistic graphics to create high impact (‘wow’ factor) and credibility

- Workplace-relevant tasks to complete

- Tools for gathering background information (emails, notes, phone calls, etc.)

- A variety of actions the learner can take (including good/bad, safe/unsafe), especially valuable if these produce outcomes which they may rarely or never meet. The eLearning is allowing them to discover safely what would happen if they risked doing this or that …

- Dynamic feedback on their actions (sounds, movement, cost, etc)

- Varied media content – sound effects, animations, videos, audio interviews, photos, etc.

- Challenges which require listening, looking, assessing evidence – in other words, giving opportunities to use judgement

- Reference material available at all times (manuals, instructional sequences, etc)

- ‘Incremental help’ provided on demand, so that at each request another hint is given

- Option to ‘give up’ if completely stuck and to have the solution explained

- Two modes of use: ‘Safe Play’ where performance is not tracked and ‘Assessment’ where possibly reference material is not accessible and their every action is logged.

- A performance report screen where the learner can review the actions they took and compare these with the actions of an expert.

- And finally immersive eLearning should be fun and challenging to use. If you can deliver a program which people talk about over coffee and return to in the hope that they can improve their performance, then you will have succeeded.

4. Examples

a) The Shake-o-Matic 4000

Each fault selected from the list gives different symptoms. The engine may or may not start and if it does, it may run poorly. The learner can take measurements, visually examine components and test, adjust or even replace them. Each action carries a cost in job time to complete it and (if an item has been replaced) in money too. Service manuals and theory of operation books are available and the learner may ask for a ‘Hint’ at any time. These build incrementally each time they are requested.

The program records every action taken and presents these on a Report screen together with their competence score assessment for the current fault. All of this data could be saved to an on-line spreadsheet or an external LMS database.

learner’s ability to recognise potential faults as they ‘fly’ around and through the equipment.

Giving access for hundreds of engineers to real equipment would also present huge logistical and practical problems whereas they can all work on this simulated equipment at the same time.

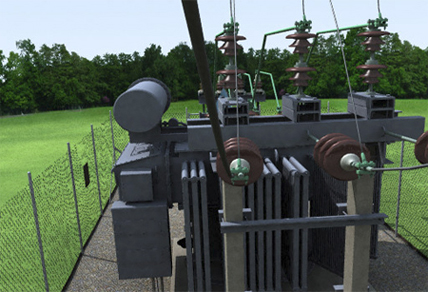

b) Electricity sub-station fault-finding

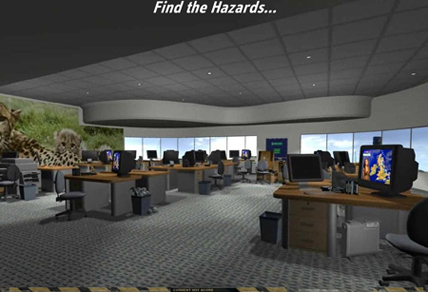

c) Fire Safety eLearning games

This is a scene from a suite of immersive games in which the learner is taken on a journey through a building, stopping at various rooms in which they must visually identify (and click on) every potential fire hazard they can spot.

Their actions are scored and they are competing against the clock. If they fail to find all the hazards in a room in 30 seconds, the program shows them where they are and explains why they pose a risk.

The photo-realistic world was built in 3D and the path through the buildings pre-determined.

d) Other examples

Game-based projects were also briefly demonstrated which covered:

- Correct choice of extinguisher to suit different fires (animated action game against the clock and scored)

- Interactive emergency evacuation game (360 degree virtual rooms in which the learner must choose the safest action or exit route, played against the clock and scored. A dynamic challenge with mounting tension)