Serious about Games

Serious about Games (Enterprise Learning 2008: Shanghai)

Abstract

People don’t really learn at a screen by reading, watching or listening. They may absorb facts but to develop understanding and competence they must be engaged, entertained and challenged to perform job-relevant tasks.

Confucius concluded: “I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand.” These words might have been written last week, not 2,500 years ago. The challenge we face today is not to try to fill the minds of our staff with facts and information but to help them develop appropriate skills and responses to the real situations they will face.

‘Serious games’ provide an environment in which adults learn more deeply by doing things.

What is a game?

The role of serious games

Before suggesting the key ingredients for effective learning games, consider some of the characteristics we should remember about a typical modern learner:

- They are impatient for results and get bored quickly

- They have high expectations, developed as they grew up in a sophisticated interactive world

- They love to compete, to be measured, to prove themselves

- Amusing, engaging experiences create lasting imagery and memories, readily recalled in future situations

For the organisation, serious games deliver safe, cost-effective practice in otherwise hazardous, expensive or inaccessible tasks … anywhere and at any time. A good game should serve a dual purpose: as a training tool to develop staff skills and judgement and as an assessment tool to measure their competence.

A serious game immerses the learner in a familiar yet virtual environment in which they may make mistakes, ask for help, refer to documentation and (when feeling ready to be measured) the chance to demonstrate their competence in a way that answering the usual multi-choice quiz questions never can.

A ‘game’ is usually defined as being a structured activity whose key components are rules, goals, challenge and interactivity. Rather than being purely for fun or entertainment, a ‘serious’ game has a serious business justification. (The word ‘game’ is an unfortunate title, perhaps giving the impression to serious-minded management that employees are going to be playing, rather than working …)

What are we trying to achieve?

Nowadays ‘information’ is often free and accessible anywhere and at any time. We don’t need to remember pecific facts until the moment we need them. The problem is that training for many organisations is still seen simply as an exchange of information from knowledgeable experts (armed with huge PowerPoint presentations) to the minds of the learners.

All organisations need competent, skilled staff but how can we best develop and assess them?

Certainly not by filling their heads with data. After all, a 2Gb memory stick will carry and instantly recall far more information than any human brain.

How about imparting ‘knowledge’, equipping people to be able to recall information in an appropriate context? Well, this is more useful than carrying around raw facts but it still lacks the vital ingredient for competent performance: judgement.

Consider this example. A technician has learned the function and purpose of every switch and indicator on a large equipment control panel. He has studied into the small hours and is now a walking technical manual. He is highly knowledgeable. But what he lacks is the ability to select and apply this vast knowledge effectively in real world situations, calling on the skills and wisdom that underpin sound judgement and which are only acquired from experience. What if our eLearning programs could not only impart knowledge but also provide opportunities to gain experience? Now there’s a challenge!

Examples include…

- Techniques and technologies for game environments

- 3D game-based ‘Fire Safety’ produced for Sky Television (use fire extinguishers with full effects, escape from a smoke-filled building in 3 minutes, spot the fire hazards)

- Interactive 3D cab simulation of a London Underground train for driver training and assessment

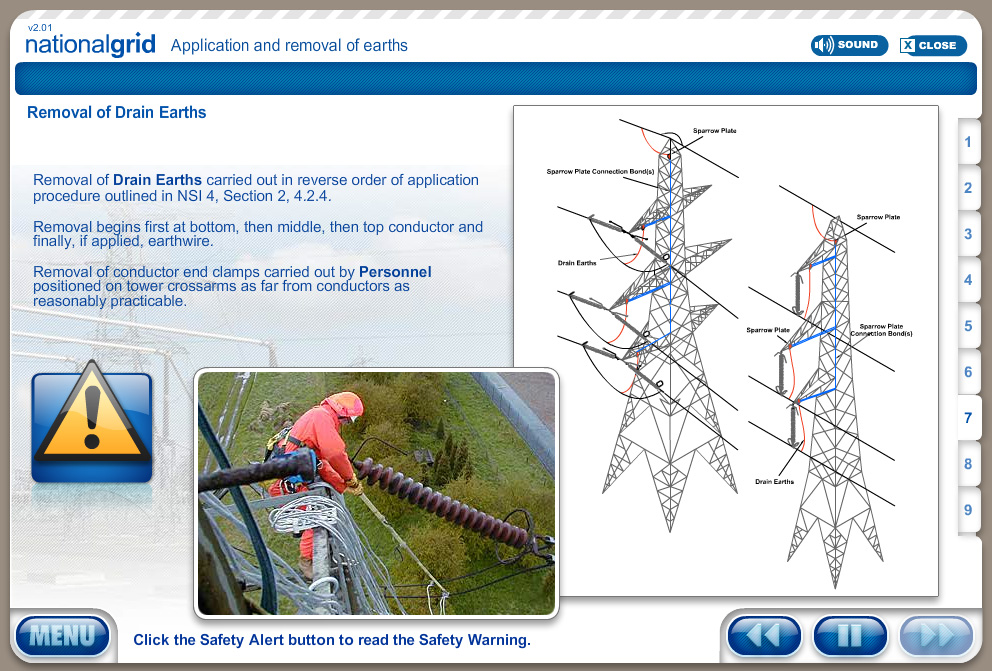

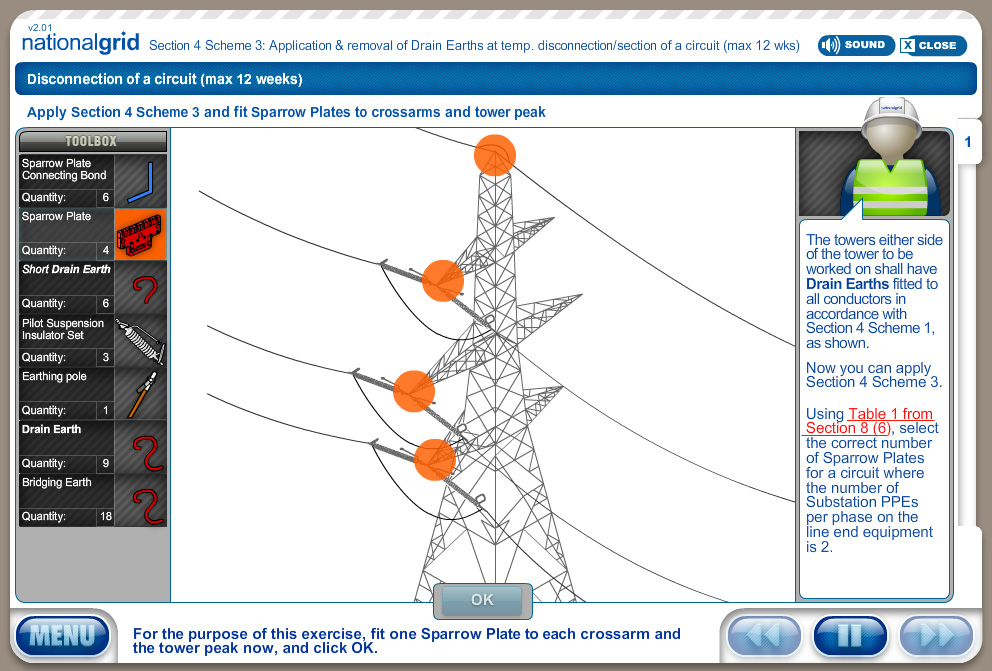

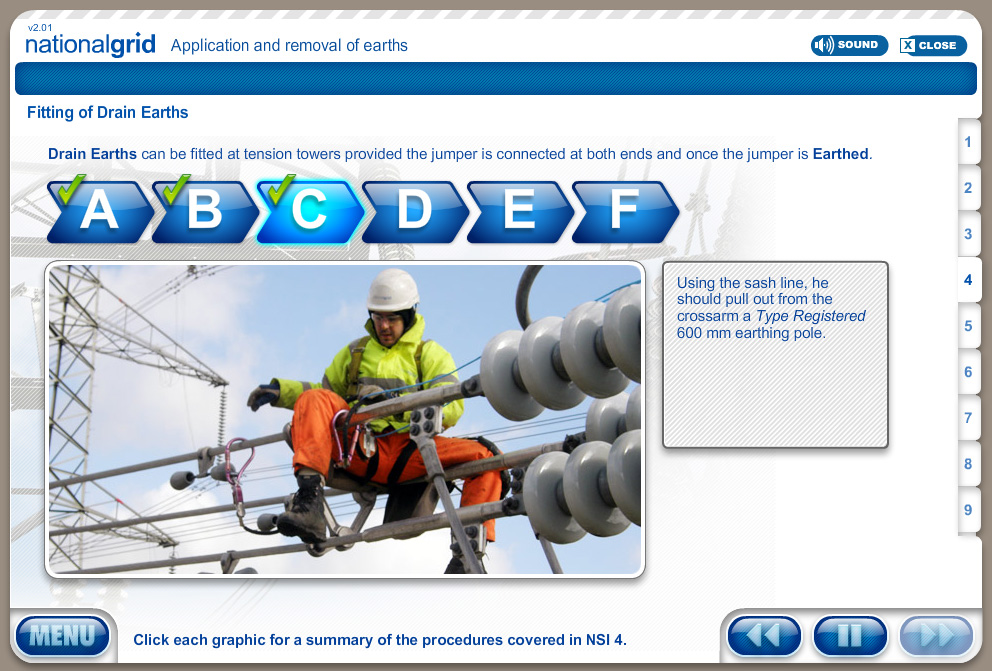

- High voltage safety procedures for engineers, with interactive task practice

- 3D office safety hazard spotting game

- Electrical fault-finding challenge on a Le Mans Cobra sports car

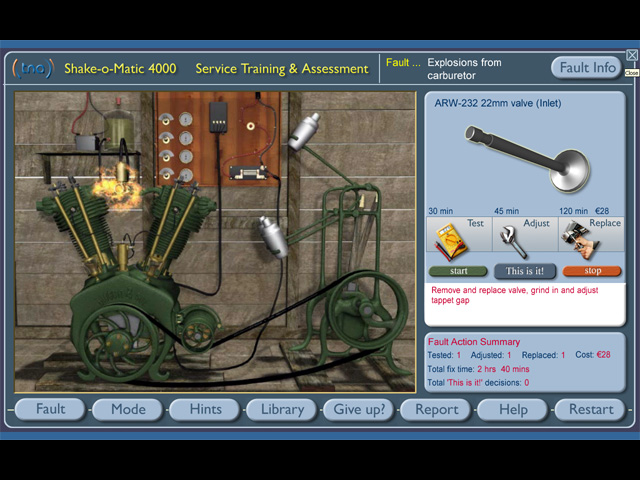

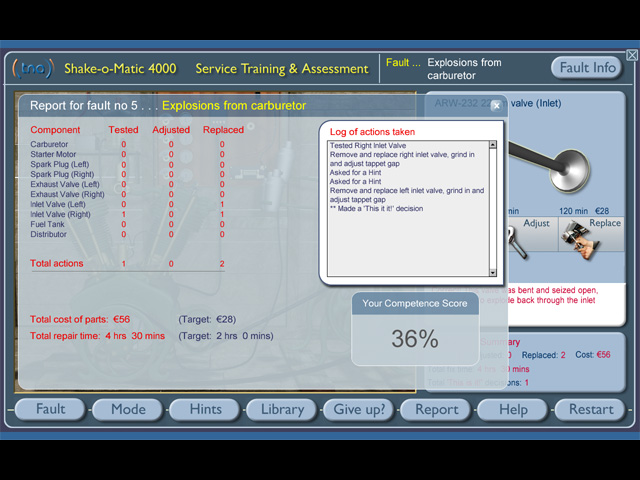

- Mechanical fault-finding challenge on the Shake-O-Matic cocktail mixer

Ten key ingredients for an effective serious game

- Present realistic imagery

The graphical scenes in which the game is played must be of the highest quality to ensure they are believable and don’t attract criticism. You need the game to be taken seriously right from the start.High quality 3D models provide stunning 2D views as well as the possibility of interactive journeys through the game environment.If the environment already exists (for example, the inside of a vehicle) then 3D modelling will not be as cost-effective as photography. With a 360 degree lens and a modest digital camera, engaging interactive panoramas can quickly be built. They are also far easier and cheaper to update than 3D modelled worlds. - Set job-relevant tasks

The game should set challenges that are typical of their real world activities, not unbelievable examples that demand great imagination to relate the game tasks to their own jobs. - Challenge the learner

… to perform well, measured against familiar targets such as task completion time, responsiveness to changing events, quantity of parts or materials used and their cost, etc. - Immerse learners immediately

Don’t force learners to read many pages of explanations before starting the game. Start with a ‘bang’ and get them started and doing something quickly. - Let experts excel

Good games should allow people who already have some degree of competence in a task or procedure to demonstrate this without hindrance or unnecessary prompting. Nothing frustrates people more than being patronised or guided when they are quite capable of handling the job themselves. - But support and guide those who need it …

The ideal model emulates the real world in which a learner would have turned to a colleague for guidance, such as a hint or a ‘tip’ on what they ought to examine or try next. Examples were shown of such ‘incremental hints’, where the learner receives increasingly more guidance each time they ask for it. All games should offer a ‘Give up’ button to allow the player a way out with their dignity intact rather than persevering and failing with no end in sight. ‘Giving up’ should then be supported with an explanation of the actions that an expert would have taken to complete the task within the targets.

- Provide access to workplace reference material

Einstein felt no need to remember his telephone number since he could always look it up in the local telephone directory …

If the game is to simulate a real working environment, it should also allow the player/learner to use the support tools they would normally have available. Learning where to go (perhaps many months in the future) to find resources, and practising how to use them may be as important a part of the game outcome as completing the tasks themselves. Resources might include servicing and theory of operation manuals, a glossary of terms, intranet search tools, fault diagnosis programs, etc.It was said that Albert Einstein felt no need to remember his telephone number since he could always look it up in the local telephone directory … probably untrue (he would have written it on his blackboard) but the concept is valid. - Give continuous feedback on game performance

Players perform best when they know exactly how they are performing against the target. Readouts of elapsed time, time remaining, parts cost and penalties incurred, etc. all add excitement and challenge and are the spur to repeat the game to do better next time. - Record and report all actions and outcomes during the game

A full record of their score and all actions taken should be shown at the end of the game. This should include each item tested, adjusted or replaced, each time they asked for a Hint, each visit to the Library to refer to a manual, etc. These actions could each carry a bonus (eg: correct part replaced) or a penalty (irrelevant or unsafe action taken, 17 visits to look at the same manual, etc).Using this rich recorded data, as an assessment tool the interactive game provides a far more revealing indication of both confidence and competence than traditional quizzes and other tests of knowledge. - Include the unexpected …

Use impact to create lasting memories with intriguing, unexpected events or incidents. Examples shown included equipment that explodes when unsafely operated or a fatal decision to return to a smoke-filled burning building terminating the game as the screen fills with smoke and escape becomes impossible.